Struggling to cope with the new flood of admissions, staff at Endell Street watched the death rate rise through January and hit a record high of 30 deaths in February-the hospital’s biggest monthly death toll ever. In all a total of 6,000 people would die in the capital before the third wave eventually receded in May. These measures would later be made standard practice by the War Office. More usefully, perhaps, she ensured that those with the flu were segregated on special wards, with screens placed around their beds, and that doctors and nurses wore face masks at all times. A disinfecting hut was set up in the courtyard, and staff were sent there to breathe in steamy vapor twice a day. Not until 1933 would scientists realize that a virus, too small for early 20th-century microscopes to detect, was the real cause.īattling to keep the hospital running as patients and staff sickened with the flu, Flora Murray insisted that the women must be meticulous about hygiene. Most doctors assumed the disease was caused by a bacterium the recently discovered Pfeiffer’s bacillus ( Haemophilus influenzae), which was sometimes present in pathology specimens, was the prime suspect. As their lungs filled with bloody fluid, they effectively drowned, commonly coughing up blood and bleeding from the nose or ears. Those who failed to rally succumbed either to the virus itself or, more often, as their lowered immune systems allowed bacteria to invade the lungs, to pneumonia, frequently within three days of showing symptoms. Some patients’ teeth and nails fell out other patients became delirious and even violent or suicidal. Unable to rise, many developed the tell-tale signs of blue-tinged lips and fingers or plum-colored blotches on their faces as their lungs became congested with blood and struggled to produce oxygen. Victims first complained of sore throats, headaches, and generalized aches but were very quickly forced to take to their beds. “It was more like a plague than influenza.” Experienced doctors agreed. “Men died like flies, in the street one moment, then three days later, dead,” said nursing orderly Nina Last. The speed with which patients succumbed to the flu, and the symptoms they displayed during its course, were completely alien to the Endell Street staff. Yet in November and December 1918, 24 men and women died of flu at times, there were as many as three deaths a day. Throughout the war years, in the face of appalling wounds and rampant infections, no more than eight soldiers died for every thousand patients treated at Endell Street-some 200 deaths in all. The death rates shocked nurses and doctors alike. All they could offer was aspirin, morphine and quinine to suppress the symptoms fluids and nourishment to keep up their patients’ strength and bedrest in the hope that the victims would beat the bug themselves.

With no antiviral medicines to combat the disease or antibiotics to treat the ensuing pneumonia, which often caused death, they were powerless to help their patients. Throughout the war, the Endell Street women had saved thousands of soldiers from death and disability through a combination of surgical expertise, pioneering infection control, skilled nursing, dedicated physical therapy and their particular brand of motivational spirit. Just when the staff should have been able to rest and recover at the end of the long, dreary war, they were working harder than ever and-worse, much worse-with the least success. Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter Extra beds were made up on the wards and immediately filled, more nurses had to be recruited to replace those who fell ill, and the doctors worked without breaks.

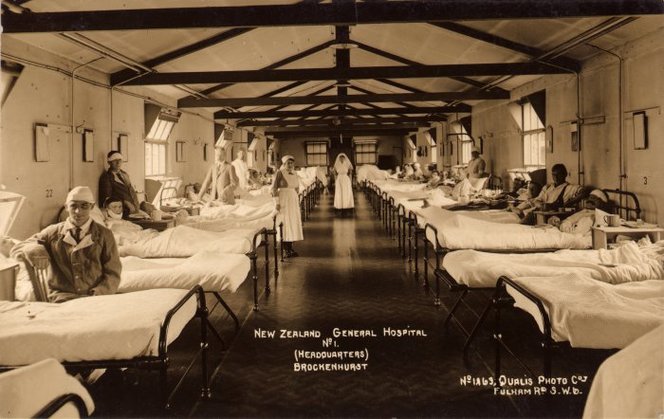

Between 50 and 60 patients at a time were seriously ill with pneumonia- often the final stage of the flu. By mid-November, “dozens of local sick” had been admitted. Local civilians crowded the casualty room, coughing and sneezing, or arrived by ambulance in a worse state as they fell victim to the disease. Now that the war’s outcome had been decided, the hospital was inundated with flu. Eleven orderlies had been struck down and admitted to “H” ward, where members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps were normally nursed. Vera Scantlebury had returned from a break to find “‘Spanish flu’ flying round the wards.” By the end of that month, with peace just within grasp, cases of the flu were “rolling in,” she noted, and the disease had spread to staff. Men and women arriving in convoys from France showed influenza symptoms in mid-October, when Dr. The first signs that the flu had returned to Endell Street had been almost overlooked in the last push toward victory. Having disappeared at the end of the summer, the virus had mutated into a deadlier, devastating new form. In Endell Street, patients and staff were developing fevers, aches and coughs at a rate that had never been seen before.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)